Monday, March 02, 2009

The UNSW Cyberspace Law and Policy Centre will be hosting the 3rd ‘Unlocking IP’ Conference at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, from 16-17 April 2009.

A registration form will be available here shortly.

The Conference will include both invited and submitted presentations. We invite proposals for papers relevant to the theme of the Conference. Please refer to the Conference Call for Papers page for details. The deadline for submission of full papers or extended abstracts is March 4, 2009.

A registration form will be available here shortly.

The Conference will include both invited and submitted presentations. We invite proposals for papers relevant to the theme of the Conference. Please refer to the Conference Call for Papers page for details. The deadline for submission of full papers or extended abstracts is March 4, 2009.

Labels: conferences, research

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Bond introduced me to the Copyright Act today (I never studied law, you see). It's got a section in it that's pretty neat from my perspective. Section 32, which I will summarise (this is probably very uncool in legal circles, to paraphrase like this, but I can 'cos I'm not a lawyer):

So to explain a little further, there's copyright under Section 32 in all works by Australian authors, and all works by any authors that publish their works in Australia before publishing them elsewhere. There's also a definition of 'Australian' (actually 'qualified person'), but it's not particularly interesting. And there's some stuff about copyright in buildings, and people who died, and works that took a long time to produce.

Anyway, what good is this to me? Well, it makes for a reasonable definition of Australian copyrighted work. Which we can then use to define the Australian public domain or the Australian commons, assuming we have a good definition of public domain or commons.

It's a very functional definition, in the sense that you can decide for a given work whether or not to include it in the class of Australian commons.

Compare this with the definition ('description' would be a better word) I used in 2006:

Thanks, Bond!

There is copyright in a work if:Yeah, that's it with about 90% of the words taken out. Legal readers, please correct me if that's wrong. (I can almost feel you shouting into the past at me from in front of your computer screens.)

- The author is Australian; or

- The first publication of the work was in Australia

So to explain a little further, there's copyright under Section 32 in all works by Australian authors, and all works by any authors that publish their works in Australia before publishing them elsewhere. There's also a definition of 'Australian' (actually 'qualified person'), but it's not particularly interesting. And there's some stuff about copyright in buildings, and people who died, and works that took a long time to produce.

Anyway, what good is this to me? Well, it makes for a reasonable definition of Australian copyrighted work. Which we can then use to define the Australian public domain or the Australian commons, assuming we have a good definition of public domain or commons.

It's a very functional definition, in the sense that you can decide for a given work whether or not to include it in the class of Australian commons.

Compare this with the definition ('description' would be a better word) I used in 2006:

Commons content that is either created by Australians, hosted in Australia, administered by Australians or Australian organisations, or pertains particularly to Australia.Yuck! Maybe that's what we mean intuitively, but that's a rather useless definition when it comes to actually applying it. Section 32 will do much better.

Thanks, Bond!

Thursday, October 02, 2008

As many readers will know, the issue of originality within Australian copyright law is currently a hotly contested issue, with the appeal in the IceTV v Nine Network decision to be heard before the High Court in two weeks time, on the 16th and 17th October.

Professor Kathy Bowrey, author of Law and Internet Cultures and House of Commons friend (and one of my supervisors), has recently penned an article on these issues, titled 'On clarifying the role of originality and fair use in 19th century UK jurisprudence: appreciating "the humble grey which emerges as the result of long controversy"'. Kathy's article has a slightly different focus: tackling originality in 19th century case law and how this concept developed. The abstract states:

Professor Kathy Bowrey, author of Law and Internet Cultures and House of Commons friend (and one of my supervisors), has recently penned an article on these issues, titled 'On clarifying the role of originality and fair use in 19th century UK jurisprudence: appreciating "the humble grey which emerges as the result of long controversy"'. Kathy's article has a slightly different focus: tackling originality in 19th century case law and how this concept developed. The abstract states:

Understanding nineteenth century precedent is one of the more difficult tasks inYou can find it in the UNSW Law Research Series here and for any readers interested in the forthcoming IceTV case this is a must-read. Two weeks to go...

copyright today. This paper considers why the nineteenth century cases and

treatises failed to clearly identify what the author owns of “right” and the

implications for the criterion of originality and for determining infringement

today.

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, High Court of Australia, infringement, research

Thursday, July 31, 2008

I've done my presentation at iSummit in the research track. My paper should be available soon on the site too.

In the same session, there was also a great talk by Juan Carlos De Martin about geo-location of web pages, but it was actually broader than that and included quantification issues. Read more about that here.

Tomorrow, the research track is going to talk about the future of research about the commons. Stay tuned.

In the same session, there was also a great talk by Juan Carlos De Martin about geo-location of web pages, but it was actually broader than that and included quantification issues. Read more about that here.

Tomorrow, the research track is going to talk about the future of research about the commons. Stay tuned.

Labels: ben, isummit08, quantification, research

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Running for 8 hours, without crashing but with a little complaining about bad web pages, my analysis analysed 191,093 web pages (not other file types like images) and found 179 pages that have rel="license" links (a semantic statement that the page is licensed) with a total of 288 rel="license" links (about 1.5 per page). This equates to 1 in 1067 pages using rel="license"

The pages were drawn randomly from the dataset, though I'm not sure that my randomisation is great - I'll look into that. As I said in a previous post, the data aims to be a broad crawl of Australian sites, but it's neither 100% complete nor 100% accurate about sites being Australian.

By my calculations, if I were to run my analysis on the whole dataset, I'd expect to find approximately 1.3 million pages using rel="licence". But keep in mind that I'm not only running the analysis over three years of data, but that data also sometimes includes the same page more than once for a given year/crawl, though much more rarely than, say, the Wayback Machine does.

And of course, this statistic says nothing about open content licensing. I'm sure, as in I know, there are lots more pages out there that don't use rel="license".

(Tech note: when doing this kind of analysis, there's a race between I/O and processor time, and ideally they're both maxed out. Over last night's analysis, the CPU load - for the last 15 minutes at least, but I think that's representative - was 58%, suggesting that I/O is so far the limiting factor.)

The pages were drawn randomly from the dataset, though I'm not sure that my randomisation is great - I'll look into that. As I said in a previous post, the data aims to be a broad crawl of Australian sites, but it's neither 100% complete nor 100% accurate about sites being Australian.

By my calculations, if I were to run my analysis on the whole dataset, I'd expect to find approximately 1.3 million pages using rel="licence". But keep in mind that I'm not only running the analysis over three years of data, but that data also sometimes includes the same page more than once for a given year/crawl, though much more rarely than, say, the Wayback Machine does.

And of course, this statistic says nothing about open content licensing. I'm sure, as in I know, there are lots more pages out there that don't use rel="license".

(Tech note: when doing this kind of analysis, there's a race between I/O and processor time, and ideally they're both maxed out. Over last night's analysis, the CPU load - for the last 15 minutes at least, but I think that's representative - was 58%, suggesting that I/O is so far the limiting factor.)

Labels: ben, quantification, research

Monday, May 19, 2008

The National Library of Australia has been crawling the Australian web (defining the Australian web is of course an issue in itself). I'm going to be running some quantification analysis over at least some of this crawl (actually plural, crawls - there is a 2005 crawl, a 2006 crawl and a 2007 crawl), probably starting with a small part of the crawl and then scaling up.

Possible outcomes from this include:

Possible outcomes from this include:

- Some meaningful consideration of how many web pages, on average, come about from a single decision to use a licence. For example, if you licence your blog and put a licence statement into your blog template, that would be one decision to use the licence, arguably one licensed work (your blog), but actually 192 web pages (with permalinks and all). I've got a few ideas about how to measure this, which I can go in to more depth about.

- How much of the Australian web is licensed, both proportionally (one page in X, one web site in X, or one 'document' in X), and in absolute terms (Y web pages, Y web sites, Y 'documents').

- Comparison of my results to proprietary search-engine based answers to the same question, to put my results in context.

- Comparison of various licensing mechanisms, including but not limited to: hyperlinks, natural language statements, dc rights in tags, rdf+xml.

- Comparison of use of various licences, and licensing elements.

- Changes in the answers to these questions over time.

Labels: ben, licensing, open content, quantification, research

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

This is one for any international readers...or, more, specifically, UK readers. Prime Minister Gordon Brown has announced that a review will be conducted into the United Kingdom National Archives. The review will consider the appropriateness of the time when records become available (this is 30 years after 'an event', which is the same here in Australia) and whether this period should be decreased. More can be found at the National Archives news page here.

Archival research is sometimes overlooked in scholarship, but it's clear that there is a wealth of information in these vaults (I personally imagine them to look something like the Hall of Prophecies from Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, although with books in place of orbs). I've been spending a lot of time on archival websites lately - the National Archives of Australia has a fantastic feature called RecordSearch that allows you to find archival documents and narrow down your search. The UK National Archives also has an excellent website - I started off planning to research Crown copyright in the UK and ended up reading perhaps a bit more than I should have about records concerning Jack the Ripper. Not for the faint-hearted researcher. Archival research is therefore a bit like spending a few hours of Wikipedia: you end up far, far away from where you started.

Benedict Atkinson's new book The True History of Copyright (review coming!) contains a lot of archival research and my own work will include this type of research. It's interesting that even though we have truly entered the age of 'digital copyright' there is still so much that we can learn from materials about history and policy from 100 years ago. Accessing and considering these types of materials can broaden both discussions about issues and the commons as well: yet another way for dwarves to stand on the shoulders of giants!

Archival research is sometimes overlooked in scholarship, but it's clear that there is a wealth of information in these vaults (I personally imagine them to look something like the Hall of Prophecies from Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, although with books in place of orbs). I've been spending a lot of time on archival websites lately - the National Archives of Australia has a fantastic feature called RecordSearch that allows you to find archival documents and narrow down your search. The UK National Archives also has an excellent website - I started off planning to research Crown copyright in the UK and ended up reading perhaps a bit more than I should have about records concerning Jack the Ripper. Not for the faint-hearted researcher. Archival research is therefore a bit like spending a few hours of Wikipedia: you end up far, far away from where you started.

Benedict Atkinson's new book The True History of Copyright (review coming!) contains a lot of archival research and my own work will include this type of research. It's interesting that even though we have truly entered the age of 'digital copyright' there is still so much that we can learn from materials about history and policy from 100 years ago. Accessing and considering these types of materials can broaden both discussions about issues and the commons as well: yet another way for dwarves to stand on the shoulders of giants!

Tuesday, October 09, 2007

Housemates Abi and Catherine, and project chief investigator Graham Greenleaf have been published in the Journal of World Intellectual Property. They were too modest to post about it themselves, but something has to be said! I mean, if I was published in the Journal of World Artificial Intelligence, well I'd want to tell everyone :) (not that there's a journal called the Journal of World Artificial Intelligence, but that's not the point!).

So without further ado, here's the link: Advance Australia Fair? The Copyright Reform Process.

Now, I'm no legal expert, and I have to admit the article was kind of over my head. But, by way of advertisement, here are some keywords I can pluck out of the paper as relevant:

So without further ado, here's the link: Advance Australia Fair? The Copyright Reform Process.

Now, I'm no legal expert, and I have to admit the article was kind of over my head. But, by way of advertisement, here are some keywords I can pluck out of the paper as relevant:

- Technological protection measures (TPMs)

- Digital rights management (DRM)

- The Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA)

- The Digital Agenda Act (forgive me for not citing correctly!)

- The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

- The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)

Labels: abi, ben, catherine, legislation, research

Friday, July 20, 2007

Ripple down rules (RDR) is a methodology for creating decision trees, in domains even experts have trouble mapping their knowledge in, by requiring the expert only to justify their correction of the system, in the context in which the particular error occurred. That's probably why the original article on ripple down rules was called Knowledge in context: a strategy for expert system maintenance.

Now, there's two possible approaches to making the RDR system probabilistic (i.e. making it predict the probability that it is wrong for a given input). First, we could try to predict the probabilities based on the structure of the RDR and which rules have fired. Alternatively, we could ask the expert explicitly for some knowledge of probabilities (in the specific context, of course).

Observational analysis

What I'm talking about here is using RDR like normal, but trying to infer probabilities based on the way it reaches its conclusion. The most obvious situation where this will work is when all the rules that conclude positive (interesting) fire and none of the rules that conclude negative (uninteresting) fire. (This does, however, mean creating a more Multiple Classification RDR type of system.) Other possibilities include watching over time to see which rules are more likely to be wrong.

These possibilities may seem week, but they may turn out to provide just enough information. Remember, any indication that some examples are more likely to be useful is good, because it can cut down the pool of potential false negatives from the whole web to something much, much smaller.

An expert opinion

The other possibility is to ask the expert in advance how likely the system is to be wrong. Now, as I discussed, this whole RDR methodology is based around the idea that experts are good at justifying themselves in context, so it doesn't make much sense to ask the expert to look at an RDR system and say in advance how likely a given analysis is to be wrong. On the other hand, it might be possible to ask the expert, when they are creating a new rule: what is the probability that the rule will be wrong (the conclusion is wrong), given that it fires (its condition is met)? And, to get a little bit more rigorous, we would ideally also like to know: what is the probability that the rule's condition will be met, given that the rule's parent fired (the rule's parent's condition was met)?

The obvious problem with this is that the expert might not be able to answer these questions, at least with any useful accuracy. On the other hand, as I said above, any little indication is useful. Also, it's worth pointing out that what we need is not primarily probabilities, but rather a ranking or ordering of the candidates for expert evaluation, so that we know which is the most likely to be useful (rather than exactly how likely it is to be useful).

Also the calculations of probabilities could turn out to be quite complex :)

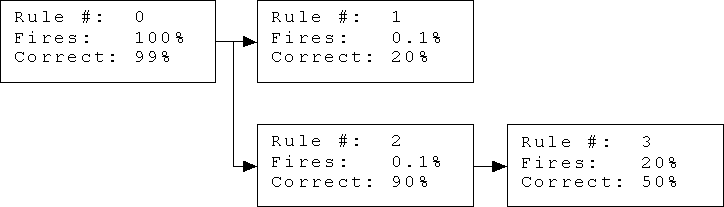

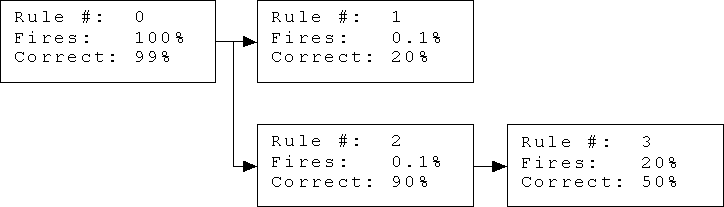

Here's what I consider a minimal RDR tree for the purposes of calculating probabilities, with some hypothetical (imaginary) given probabilities.

Let me explain. Rule 0 is the default rule (the starting point for all RDR systems). It fires 100% of the time, and in this case it is presumed to be right 99% of the time (simulating the needle-in-a-haystack scenario). Rules 1 and 2 are exceptions to rule 0, and will be considered only when rule 0 fires (which is all the time because it is the default rule). Rule 3 is an exception to rule 2, and will be considered only when rule 2 fires.

The conclusions of rules 0 and 3 are (implicitly) 'hay' (uninteresting), while the conclusions of rules 1 and 2 are (implicitly) 'needle' (interesting). This is because the conclusion of every exception rule needs to be different from the conclusion of the parent rule.

The percentage for 'Fires' represents the expert's opinion of how likely the rule is to fire (have its condition met) given that the rule is reached (its parent is reached and fires). The percentage for 'Correct' represents the expert's opinion of how likely the rule's conclusion is to be correct, given that the rule is reached and fires.

With this setup, you can start to calculate some interesting probabilities, given knowledge of which rules fire for a given example. For example, what is the probability of 'needle' given that rules 1 and 2 both fire, but rule 3 doesn't? (This is assumedly the most positive indication of 'needle' we can get.) What difference would it make if rule 3 did fire? If you can answer either of these questions, leave a comment.

If no rules fire, for example, the probability of 'needle' is 0.89%, which is only very slightly less than the default probability of 'needle' before using the system, which was 1%. Strange, isn't it?

Now, there's two possible approaches to making the RDR system probabilistic (i.e. making it predict the probability that it is wrong for a given input). First, we could try to predict the probabilities based on the structure of the RDR and which rules have fired. Alternatively, we could ask the expert explicitly for some knowledge of probabilities (in the specific context, of course).

Observational analysis

What I'm talking about here is using RDR like normal, but trying to infer probabilities based on the way it reaches its conclusion. The most obvious situation where this will work is when all the rules that conclude positive (interesting) fire and none of the rules that conclude negative (uninteresting) fire. (This does, however, mean creating a more Multiple Classification RDR type of system.) Other possibilities include watching over time to see which rules are more likely to be wrong.

These possibilities may seem week, but they may turn out to provide just enough information. Remember, any indication that some examples are more likely to be useful is good, because it can cut down the pool of potential false negatives from the whole web to something much, much smaller.

An expert opinion

The other possibility is to ask the expert in advance how likely the system is to be wrong. Now, as I discussed, this whole RDR methodology is based around the idea that experts are good at justifying themselves in context, so it doesn't make much sense to ask the expert to look at an RDR system and say in advance how likely a given analysis is to be wrong. On the other hand, it might be possible to ask the expert, when they are creating a new rule: what is the probability that the rule will be wrong (the conclusion is wrong), given that it fires (its condition is met)? And, to get a little bit more rigorous, we would ideally also like to know: what is the probability that the rule's condition will be met, given that the rule's parent fired (the rule's parent's condition was met)?

The obvious problem with this is that the expert might not be able to answer these questions, at least with any useful accuracy. On the other hand, as I said above, any little indication is useful. Also, it's worth pointing out that what we need is not primarily probabilities, but rather a ranking or ordering of the candidates for expert evaluation, so that we know which is the most likely to be useful (rather than exactly how likely it is to be useful).

Also the calculations of probabilities could turn out to be quite complex :)

Here's what I consider a minimal RDR tree for the purposes of calculating probabilities, with some hypothetical (imaginary) given probabilities.

Let me explain. Rule 0 is the default rule (the starting point for all RDR systems). It fires 100% of the time, and in this case it is presumed to be right 99% of the time (simulating the needle-in-a-haystack scenario). Rules 1 and 2 are exceptions to rule 0, and will be considered only when rule 0 fires (which is all the time because it is the default rule). Rule 3 is an exception to rule 2, and will be considered only when rule 2 fires.

The conclusions of rules 0 and 3 are (implicitly) 'hay' (uninteresting), while the conclusions of rules 1 and 2 are (implicitly) 'needle' (interesting). This is because the conclusion of every exception rule needs to be different from the conclusion of the parent rule.

The percentage for 'Fires' represents the expert's opinion of how likely the rule is to fire (have its condition met) given that the rule is reached (its parent is reached and fires). The percentage for 'Correct' represents the expert's opinion of how likely the rule's conclusion is to be correct, given that the rule is reached and fires.

With this setup, you can start to calculate some interesting probabilities, given knowledge of which rules fire for a given example. For example, what is the probability of 'needle' given that rules 1 and 2 both fire, but rule 3 doesn't? (This is assumedly the most positive indication of 'needle' we can get.) What difference would it make if rule 3 did fire? If you can answer either of these questions, leave a comment.

If no rules fire, for example, the probability of 'needle' is 0.89%, which is only very slightly less than the default probability of 'needle' before using the system, which was 1%. Strange, isn't it?

Labels: artificial intelligence, ben, research

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

In a previous post, I talked about the problems of finding commons in the deep web; now I want to talk about some possible solutions to these problems.

Ripple Down Rules

Ripple down rules is a knowledge acquisition methodology developed at the University of New South Wales. It's really simple - it's about incrementally creating a kind of decision tree based on an expert identifying what's wrong with the current decision tree. It works because the expert only needs to justify their conclusion that the current system is wrong in a particular case, rather than identify a universal correction that needs to be made, and also the system is guaranteed to be consistent with the expert's evaluation of all previously seen data (though overfitting can obviously still be a problem).

The application of ripple down rules to deep web commons is simply this: once you have a general method for flattened web forms, you can use the flattened web form as input to the ripple down rules system and have the system decide if the web form hides commons.

But how do you create rules from a list of text strings without even a known size (for example, there could be any number of options in a select input (dropdown list), and any number of select inputs in a form). The old "IF weather = 'sunny' THEN play = 'tennis'" type of rule doesn't work. One solution is to make the rule conditions more like questions, with rules like "IF select-option contains-word 'license' THEN form = 'commons'" (this is a suitable rule for Advanced Google Code Search). Still, I'm not sure this is the best way to express conditions. To put it another way, I'm still not sure that extracting a list of strings, of indefinite length, is the right way to flatten the form (see this post). Contact me if you know of a better way.

A probabilistic approach?

As I have said, one of the most interesting issues I'm facing is the needle in a haystack problem, where we're searching for (probably) very few web forms that hide commons, in a very very big World Wide Web full of all kinds of web forms.

Of course computers are good at searching through lots of data, but here's the problem: while you're training your system, you need examples of the system being wrong, so you can correct it. But how do you know when it's wrong? Basically, you have to look at examples and see if you (or the expert) agree with the system. Now in this case we probably want to look through all the positives (interesting forms), so we can use any false positives (uninteresting forms) to train the system, but that will quickly train the system to be conservative, which has two drawbacks. Firstly, we'd rather it wasn't conservative because we'd be more likely to find more interesting forms. Secondly, because we'll be seeing less errors in the forms classified as interesting, we have less examples to use to train the system. And to find false negatives (interesting forms incorrectly classified as uninteresting), the expert has to search through all the examples the system doesn't currently think are interesting (and that's about as bad as having no system at all, and just browsing the web).

So the solution seems, to me, to be to change the system, so that it can identify the web form that it is most likely to be wrong about. Then we can get the most bang (corrections) for our buck (our expert's time). But how can anything like ripple down rules do that?

Probabilistic Ripple Down Rules

This is where I think the needle in a haystack problem can actually be an asset. I don't know how to make a system that can tell how close an example is to the boundary between interesting and uninteresting (the boundary doesn't really exist, even). But it will be a lot easier to make a system that predicts how likely an example is to be an interesting web form.

This way, if the most likely of the available examples is interesting, it will be worth looking at (of course), and if it's classified as not interesting, it's the most likely to have been incorrectly classified, and provide a useful training example.

I will talk about how it might be possible to extract probabilities from a ripple down rules system, but this post is long enough already, so I'll leave that for another post.

Ripple Down Rules

Ripple down rules is a knowledge acquisition methodology developed at the University of New South Wales. It's really simple - it's about incrementally creating a kind of decision tree based on an expert identifying what's wrong with the current decision tree. It works because the expert only needs to justify their conclusion that the current system is wrong in a particular case, rather than identify a universal correction that needs to be made, and also the system is guaranteed to be consistent with the expert's evaluation of all previously seen data (though overfitting can obviously still be a problem).

The application of ripple down rules to deep web commons is simply this: once you have a general method for flattened web forms, you can use the flattened web form as input to the ripple down rules system and have the system decide if the web form hides commons.

But how do you create rules from a list of text strings without even a known size (for example, there could be any number of options in a select input (dropdown list), and any number of select inputs in a form). The old "IF weather = 'sunny' THEN play = 'tennis'" type of rule doesn't work. One solution is to make the rule conditions more like questions, with rules like "IF select-option contains-word 'license' THEN form = 'commons'" (this is a suitable rule for Advanced Google Code Search). Still, I'm not sure this is the best way to express conditions. To put it another way, I'm still not sure that extracting a list of strings, of indefinite length, is the right way to flatten the form (see this post). Contact me if you know of a better way.

A probabilistic approach?

As I have said, one of the most interesting issues I'm facing is the needle in a haystack problem, where we're searching for (probably) very few web forms that hide commons, in a very very big World Wide Web full of all kinds of web forms.

Of course computers are good at searching through lots of data, but here's the problem: while you're training your system, you need examples of the system being wrong, so you can correct it. But how do you know when it's wrong? Basically, you have to look at examples and see if you (or the expert) agree with the system. Now in this case we probably want to look through all the positives (interesting forms), so we can use any false positives (uninteresting forms) to train the system, but that will quickly train the system to be conservative, which has two drawbacks. Firstly, we'd rather it wasn't conservative because we'd be more likely to find more interesting forms. Secondly, because we'll be seeing less errors in the forms classified as interesting, we have less examples to use to train the system. And to find false negatives (interesting forms incorrectly classified as uninteresting), the expert has to search through all the examples the system doesn't currently think are interesting (and that's about as bad as having no system at all, and just browsing the web).

So the solution seems, to me, to be to change the system, so that it can identify the web form that it is most likely to be wrong about. Then we can get the most bang (corrections) for our buck (our expert's time). But how can anything like ripple down rules do that?

Probabilistic Ripple Down Rules

This is where I think the needle in a haystack problem can actually be an asset. I don't know how to make a system that can tell how close an example is to the boundary between interesting and uninteresting (the boundary doesn't really exist, even). But it will be a lot easier to make a system that predicts how likely an example is to be an interesting web form.

This way, if the most likely of the available examples is interesting, it will be worth looking at (of course), and if it's classified as not interesting, it's the most likely to have been incorrectly classified, and provide a useful training example.

I will talk about how it might be possible to extract probabilities from a ripple down rules system, but this post is long enough already, so I'll leave that for another post.

Labels: artificial intelligence, ben, research

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Today I just wanted to take a brief look at some of the problems I'm finding myself tackling with the deep web commons question. There's two main ones, from quite different perspectives, but for both I can briefly describe my current thoughts.

Flattening a web form

The first problem is that of how to represent a web form in such a way that it can be used as an input to an automated system that can evaluate it. Ideally, in machine learning, you have a set of attributes that form a vector, and then you use that as the input to your algorithm. Like in tic-tac-toe, you might represent a cross by -1, a naught by +1, and an empty space by 0, and then the game can be represented by 9 of these 'attributes'.

But for web forms it's not that simple. There are a few parts of the web form that are different from each other. I've identified these potentially useful places, of which there may be one or more, and all of which take the form of text. These are just the ones I needed when considering Advanced Google Code Search:

But as far as I can tell, text makes for bad attributes. Numerical is much better. As far as I can tell. But I'll talk about that more when I talk about ripple down rules.

A handful of needles in a field of haystacks

The other problem is more about what we're actually looking for. We're talking about web forms that hide commons content. Well the interesting this about that is that there's bound to be very few, compared to the rest of the web forms on the Internet. Heck, they're not even all for searching. Some are for buying things. Some are polls.

And so, if, as seems likely, most web forms are uninteresting, if we need to enlist an expert to train the system, the expert is going to be spending most of the time looking at uninteresting examples.

This makes it harder, but in an interesting way: if I can find some way to have the system, while it's in training, find the most likely candidate of all the possible candidates, it could solve this problem. And that would be pretty neat.

Flattening a web form

The first problem is that of how to represent a web form in such a way that it can be used as an input to an automated system that can evaluate it. Ideally, in machine learning, you have a set of attributes that form a vector, and then you use that as the input to your algorithm. Like in tic-tac-toe, you might represent a cross by -1, a naught by +1, and an empty space by 0, and then the game can be represented by 9 of these 'attributes'.

But for web forms it's not that simple. There are a few parts of the web form that are different from each other. I've identified these potentially useful places, of which there may be one or more, and all of which take the form of text. These are just the ones I needed when considering Advanced Google Code Search:

- Form text. The actual text of the web form. E.g. "Advanced Code Search About Google Code Search Find results with the regular..."

- Select options. Options in drop-down boxes. E.g. "any language", "Ada", "AppleScript", etc.

- Field names. Underlying names of the various fields. E.g. "as_license_restrict", "as_license", "as_package".

- Result text. The text of each search result. E.g. (if you search for "commons"): "shibboleth-1.3.2-install/.../WrappedLog.java - 8 identical 26: package..."

- Result link name. Hyperlinks in the search results. E.g. "8 identical", "Apache"

But as far as I can tell, text makes for bad attributes. Numerical is much better. As far as I can tell. But I'll talk about that more when I talk about ripple down rules.

A handful of needles in a field of haystacks

The other problem is more about what we're actually looking for. We're talking about web forms that hide commons content. Well the interesting this about that is that there's bound to be very few, compared to the rest of the web forms on the Internet. Heck, they're not even all for searching. Some are for buying things. Some are polls.

And so, if, as seems likely, most web forms are uninteresting, if we need to enlist an expert to train the system, the expert is going to be spending most of the time looking at uninteresting examples.

This makes it harder, but in an interesting way: if I can find some way to have the system, while it's in training, find the most likely candidate of all the possible candidates, it could solve this problem. And that would be pretty neat.

Labels: ben, deep web, research

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

My previous two posts, last week, talked about my research, but didn't really talk about what I'm researching at the moment.

The deep web

Okay, so here's what I'm looking at. It's called the deep web, and it refers to the web documents that the search engines don't know about.

Sort of.

Actually, when the search engines find these documents, they really become part of the surface web, in a process sometimes called surfacing. Now I'm sure you're wondering: what kinds of documents can't search engines find, if they're the kind of documents anyone can browse to? The simple answer is: documents that no other pages link to. But a more realistic answer is that it's documents hidden in databases, that you have to do searches on the site to find. They'll generally have URLs, and you can link to them, but unless someone does, they're part of the deep web.

Now this is just a definition, and not particularly interesting in itself. But it turns out (though I haven't counted, myself) that there are more accessible web pages in the deep web than in the surface web. And they're not beyond the reach of automated systems - the systems just have to know the right questions to ask and the right place to ask the question. Here's an example, close to Unlocking IP. Go to AEShareNet and do a search, for anything you like. The results you get (when you navigate to them) are documents that you can only find by searching like this, or if someone else has done this, found the URL, and then linked to it on the web.

Extracting (surfacing) deep web commons

So when you consider how many publicly licensed documents may be in the deep web, it becomes an interesting problem from both the law / Unlocking IP perspective and from the computer science, which I'm really happy about. What I'm saying here is that I'm investigating ways of making automated systems to discover deep web commons. And it's not simple.

Lastly, some examples

I wanted to close with two web sites that I think are interesting in the context of deep web commons. First, there's SourceForge, which I'm sure the Planet Linux Australia readers will know (for the rest: it's a repository for open source software). It's interesting, because their advanced search feature really doesn't give many clues about it being a search for open source software.

And then there's the Advanced Google Code Search, which searches for publicly available source code, which generally means free or open source, but sometimes just means available, because Google can't figure out what the licence is. This is also interesting because it's not what you'd normally think of as deep web content. After all Google's just searching for stuff it found on the web, right? Actually, I class this as deep web content because Google is (mostly) looking inside zip files to find the source code, so it's not stuff you can find in regular search.

This search, as compared to SourceForge advanced search, makes it very clear you're searching for things that are likely to be commons content. In fact, I came up with 6 strong pieces of evidence that I can say leads me to believe Google Code Search is commons related.

(As a challenge to my readers, see how many pieces of evidence you can find that the Advanced Google Code Search is a search for commons (just from the search itself), and post a comment).

The deep web

Okay, so here's what I'm looking at. It's called the deep web, and it refers to the web documents that the search engines don't know about.

Sort of.

Actually, when the search engines find these documents, they really become part of the surface web, in a process sometimes called surfacing. Now I'm sure you're wondering: what kinds of documents can't search engines find, if they're the kind of documents anyone can browse to? The simple answer is: documents that no other pages link to. But a more realistic answer is that it's documents hidden in databases, that you have to do searches on the site to find. They'll generally have URLs, and you can link to them, but unless someone does, they're part of the deep web.

Now this is just a definition, and not particularly interesting in itself. But it turns out (though I haven't counted, myself) that there are more accessible web pages in the deep web than in the surface web. And they're not beyond the reach of automated systems - the systems just have to know the right questions to ask and the right place to ask the question. Here's an example, close to Unlocking IP. Go to AEShareNet and do a search, for anything you like. The results you get (when you navigate to them) are documents that you can only find by searching like this, or if someone else has done this, found the URL, and then linked to it on the web.

Extracting (surfacing) deep web commons

So when you consider how many publicly licensed documents may be in the deep web, it becomes an interesting problem from both the law / Unlocking IP perspective and from the computer science, which I'm really happy about. What I'm saying here is that I'm investigating ways of making automated systems to discover deep web commons. And it's not simple.

Lastly, some examples

I wanted to close with two web sites that I think are interesting in the context of deep web commons. First, there's SourceForge, which I'm sure the Planet Linux Australia readers will know (for the rest: it's a repository for open source software). It's interesting, because their advanced search feature really doesn't give many clues about it being a search for open source software.

And then there's the Advanced Google Code Search, which searches for publicly available source code, which generally means free or open source, but sometimes just means available, because Google can't figure out what the licence is. This is also interesting because it's not what you'd normally think of as deep web content. After all Google's just searching for stuff it found on the web, right? Actually, I class this as deep web content because Google is (mostly) looking inside zip files to find the source code, so it's not stuff you can find in regular search.

This search, as compared to SourceForge advanced search, makes it very clear you're searching for things that are likely to be commons content. In fact, I came up with 6 strong pieces of evidence that I can say leads me to believe Google Code Search is commons related.

(As a challenge to my readers, see how many pieces of evidence you can find that the Advanced Google Code Search is a search for commons (just from the search itself), and post a comment).

Labels: ben, deep web, research

Friday, July 06, 2007

Those of you who have been paying (very) close attention would have noticed that there was one thing missing from yesterday's post - the very same topic on which I've been published: quantification of online commons.

This is set to be a continuing theme in my research. Not because it's particularly valuable in the field of computer science, but because in the (very specific) field of online commons research, no one else seems to be doing much. (If you know something I don't about where to look for the research on this, please contact me now!)

I wish I could spend more time on this. What I'd do if I could would be another blog post altogether. Suffice it to say that I envisaged a giant machine (completely under my control), frantically running all over the Internets counting documents and even discovering new types of licences. If you want to hear more, contact me, or leave a comment here and convince me to post on it specifically.

So what do I have to say about this? Actually, so much that the subject has its own page. It's on unlockingip.org, here. It basically surveys what's around on the subject, and a fair bit of that is my research. But I would love to hear about yours or any one else's, published, unpublished, even conjecture.

Just briefly, here's what you can currently find on the unlockingip.org site:

I'm also interested in the methods of quantification. With the current technologies, what is the best way to find out, for any given licence, how many documents (copyrighted works) are available with increased public rights? This is something I need to put to Creative Commons, because their licence statistics page barely addresses this issue.

This is set to be a continuing theme in my research. Not because it's particularly valuable in the field of computer science, but because in the (very specific) field of online commons research, no one else seems to be doing much. (If you know something I don't about where to look for the research on this, please contact me now!)

I wish I could spend more time on this. What I'd do if I could would be another blog post altogether. Suffice it to say that I envisaged a giant machine (completely under my control), frantically running all over the Internets counting documents and even discovering new types of licences. If you want to hear more, contact me, or leave a comment here and convince me to post on it specifically.

So what do I have to say about this? Actually, so much that the subject has its own page. It's on unlockingip.org, here. It basically surveys what's around on the subject, and a fair bit of that is my research. But I would love to hear about yours or any one else's, published, unpublished, even conjecture.

Just briefly, here's what you can currently find on the unlockingip.org site:

- My SCRIT-ed paper

- My research on the initial uptake of the Creative Commons version 2.5 (Australia) licence

- Change in apparent Creative Commons usage, June 2006 - March 2007

- Creative Commons semi-official statistics

I'm also interested in the methods of quantification. With the current technologies, what is the best way to find out, for any given licence, how many documents (copyrighted works) are available with increased public rights? This is something I need to put to Creative Commons, because their licence statistics page barely addresses this issue.

Labels: ben, quantification, research

Thursday, July 05, 2007

Recently, I've been pretty quiet on this blog, and people have started noticing and suggested I post more. Of course I don't need to point out what my response was...

The reason I haven't been blogging much (apart from laziness, which can never be ruled out) is that The House of Commons has become something of an IP blog. Okay, it sounds obvious, I know. And, as it seems I say at every turn, I have no background in law, and my expertise is in computer science and software engineering. And one of the unfortunate aspects of the blog as a medium is that you don't really know who's reading it. The few technical posts I've done haven't generated much feedback, but then maybe that's my fault for posting so rarely that the tech folks have stopped reading.

So the upshot of this is a renewed effort by me to post more often, even if it means technical stuff that doesn't make sense to all our readers. It's not like I'm short of things to say.

To start with, in the remainder of this post, I want to try to put in to words, as generally as possible, what I consider my research perspective to be...

Basically what I'm most interested in is the discovery of online documents that we might consider to be commons. (But remember, I'm not the law guy, so I'm trying not to concern myself with that definition.) I think it's really interesting, technically, because it's so difficult to say (in any automated, deterministic way, without the help of an expert - a law expert in this case).

And my my computer science supervisor, Associate Professor Achim Hoffman, has taught me that computer science research needs to be as broad in application as possible, so as I investigate these things, I'm sparing a thought for their applicability to areas other than commons and even law.

In upcoming posts, I'll talk about the specifics of my research focus, some of the specific problems that make it interesting, possible solutions, and some possible research papers that might come out of it in the medium term.

The reason I haven't been blogging much (apart from laziness, which can never be ruled out) is that The House of Commons has become something of an IP blog. Okay, it sounds obvious, I know. And, as it seems I say at every turn, I have no background in law, and my expertise is in computer science and software engineering. And one of the unfortunate aspects of the blog as a medium is that you don't really know who's reading it. The few technical posts I've done haven't generated much feedback, but then maybe that's my fault for posting so rarely that the tech folks have stopped reading.

So the upshot of this is a renewed effort by me to post more often, even if it means technical stuff that doesn't make sense to all our readers. It's not like I'm short of things to say.

To start with, in the remainder of this post, I want to try to put in to words, as generally as possible, what I consider my research perspective to be...

Basically what I'm most interested in is the discovery of online documents that we might consider to be commons. (But remember, I'm not the law guy, so I'm trying not to concern myself with that definition.) I think it's really interesting, technically, because it's so difficult to say (in any automated, deterministic way, without the help of an expert - a law expert in this case).

And my my computer science supervisor, Associate Professor Achim Hoffman, has taught me that computer science research needs to be as broad in application as possible, so as I investigate these things, I'm sparing a thought for their applicability to areas other than commons and even law.

In upcoming posts, I'll talk about the specifics of my research focus, some of the specific problems that make it interesting, possible solutions, and some possible research papers that might come out of it in the medium term.