Wednesday, April 22, 2009

IceTV's General Manager, Matt Kossatz notes:

“Today’s decision is the news that we (IceTV), our staff and our loyal subscribers have waited 3 long years to hear. We would like to thank everyone for their continued support.”UPDATE: THE HIGH COURT DECISION IS AVAILABLE HERE (6-0!). We will read and digest the judgment and get back to you!

More information about the case's history is available in our last few posts about IceTV here and here.

Sunday, October 19, 2008

The proceedings began on Thursday morning and the Australian Digital Alliance and Telstra were both granted amicus status, the ADA for IceTV and Telstra for Nine Network. David Catterns, the barrister who successfully argued for CAL in the recent CAL v NSW decision appeared for Telstra. The hearing took the better part of Thursday and Friday and the transcript of the Thursday proceedings can be found on AustLII here.

As I said, this is the first of a few posts on the hearing, so I will have more of a discussion up within the next few days.

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, High Court of Australia

Thursday, October 02, 2008

Professor Kathy Bowrey, author of Law and Internet Cultures and House of Commons friend (and one of my supervisors), has recently penned an article on these issues, titled 'On clarifying the role of originality and fair use in 19th century UK jurisprudence: appreciating "the humble grey which emerges as the result of long controversy"'. Kathy's article has a slightly different focus: tackling originality in 19th century case law and how this concept developed. The abstract states:

Understanding nineteenth century precedent is one of the more difficult tasks inYou can find it in the UNSW Law Research Series here and for any readers interested in the forthcoming IceTV case this is a must-read. Two weeks to go...

copyright today. This paper considers why the nineteenth century cases and

treatises failed to clearly identify what the author owns of “right” and the

implications for the criterion of originality and for determining infringement

today.

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, High Court of Australia, infringement, research

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Labels: cases, catherine, High Court of Australia

Tuesday, September 09, 2008

"The (Lexicon) took an enormous amount of my work and added virtually noAccording to reports it is likely that the decision will be appealed. More can be read at the Sydney Morning Herald here or for those in the mood for some lighter reading, at the Internet Movie Database here.

original commentary of its own. Now the court has ordered that it must not be

published"...

"Many books have been published which offer original insights into the

world of Harry Potter. The Lexicon just is not one of them."

Labels: books, cases, catherine, fair use, infringement

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

Another copyright case in the High Court? Be afraid...be very afraid.

In May 2008 the Full Federal Court handed down its decision in the IceTV case, overturning the first instance decision and cementing (or so we thought...and so we will probably find out again) the far reach of copyright protection in

The Full Bench noted that the question of substantiality depends more upon the quality rather the quantity of what is taken:

"When the quality of the material taken by Ice is considered, the substantiality of the part taken becomes even clearer" (at [115]).

Apparently by 'copying' week to week changes IceTV "appropriated the most creative elements of the skill and labour utilised by Nine in creating the Weekly Schedules" (at [115]).

Will IceTV get up on appeal? Magic 8 ball says 'outlook not so good'...but the battle rages on...and we wait with bated breath.Kim Weatherall has written some excellent commentary about the case here and here. It is also worthwhile to take a look at IceTV Iced: Kangaroos Hopping Mad by U.S. copyright guru, Bill Patry.

[Update: The High Court transcript is now available. Further reading at Peter Vogel's blog (IceTV's former CTO) and slides from this presentation by David Lindsay which Cath linked to earlier.]

Thursday, August 14, 2008

THE “IP” Court Supports Enforceability of CC Licenses

Brian Rowe, August 13th, 2008The United States Court of Appeals held that “Open Source” or public license licensors are entitled to copyright infringement relief.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), the leading IP court in the United States, has upheld a free copyright license, while explicitly pointing to the work of Creative Commons and others. The Court held that free licenses such as the CC licenses set conditions (rather than covenants) on the use of copyrighted work. As a result, licensors using public licenses are able to seek injunctive relief for alleged copyright infringement, rather than being limited to traditional contract

remedies.Creative Commons founder Lawrence Lessig explained the theory of all free software, open source, and Creative Commons licenses upheld by the court: “When you violate the condition, the license disappears, meaning you’re simply a copyright infringer. This is the theory of the GPL and all CC licenses. Put precisely, whether or not they are also contracts, they are copyright licenses which expire if you fail to abide by the terms of the license.” Lessig said the ruling provided “important clarity and certainty by a critically important US Court.”

Today’s ruling vacated the district court’s decision and affirmed the availability of remedies based on copyright law for violations of open licenses. The federal court noted that ignoring attribution requirements contained in the license caused reputation and economic harm to the original licensor. This opinion demonstrates a strong understanding of a basic economic principles of the internet; attribution is a valuable economic right in the information economy. Read the full opinion.(PDF)

Creative Commons filed a friends of the court brief in this case. Thanks to all the cosponsors Linux Foundation, The Open Source Initiative, Software Freedom Law Center, the Perl Foundation and Wikimedia Foundation. Significant pro bono work on this brief was provided by Anthony T. Falzone and Christopher K. Ridder of Stanford’s Center for Internet & Society. Read the full brief.

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, Creative Commons, enforcement, free software, open source

Thursday, August 07, 2008

So at the end of my last post I suggested that, if the Government introduced new free use provisions, based on the UK legislative model, to deal with the decision of the High Court in CAL v NSW, then there may be some constitutional problems in doing so. I mentioned two provisions - section 51(xviii), the constitutional copyright power; and section 51(xxxi), the power with respect to acquisition of property on just terms.

Any arguments with respect to section 51(xviii) can arguably be easily dealt with. What's interesting about this power is that, for a long time, it was believed that the Parliament could actually do very little with respect to copyrights because of the narrow interpretation given in the decision of Attorney-General (NSW) ex rel Tooth & Co Ltd v Brewery Employees' Union of NSW [1908] HCA 94; (1908) 6 CLR 469. In that case it was found that the union label trade mark wasn't valid because such marks were not around in 1900, when the Constitution was framed. On that basis, for about eighty-five years it was believed that section 51(xviii) gave the Parliament very narrow power with respect to making IP laws. However, the 1994 decision Nintendo Co Ltd v Centronics Systems Pty Ltd [1994] HCA 27; (1994) 181 CLR 134 and then the subsequent 2000 decision Grain Pool of Western Australia v Commonwealth [2000] HCA 14; 202 CLR 479 - revealed that the HCA believed that section 51(xviii) was quite a wide power, leading to broader concerns that there might not actually be any limits on section 51(xviii).

As such, given this broad interpretation, it would be unlikely that such free use exceptions would fall foul of section 51(xviii), unless some sort of constitutional argument could be raised that the term "copyrights" as it appears in the Constitution requires that remuneration be given to the copyright owner. That, however, would probably cause all types of chaos, and is therefore unlikely. It would be interesting to run though...however, in light of the CAL v NSW decision, I am in no hurry to get another copyright case before the HCA.

It is the second provision, however, that may cause constitutional difficulties for these types of exception. Section 51(xxxi) has occasionally popped up in IP decisions over the last fifteen years (see Australian Tape Manufacturers Association Ltd v Commonwealth [1993] HCA 10; (1993) 176 CLR 480 and Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment [2005] HCA 58; (2005) 221 ALR 448). This constitutional section was actually mentioned at several points in the joint judgment of CAL v NSW:

At [57]: In any event, with an echo of s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution, the Spicer Committee made its recommendation for government use of copyright material in the following terms:[51]

"The Solicitor-General of the Commonwealth has expressed the view that the

Commonwealth and the States should be empowered to use copyright material for

any purposes of the Crown, subject to the payment of just terms to be fixed, in

the absence of agreement, by the Court. A majority of us agree with that view.

The occasions on which the Crown may need to use copyright material are varied

and many. Most of us think that it is not possible to list those matters which

might be said to be more vital to the public interest than others. At the same

time, the rights of the author should be protected by provisions for the payment

of just compensation to be fixed in the last resort by the Court." (emphasis

added).

And then again at paras [68] - [69]:

The purpose of the scheme is to enable governments to use material subject to copyright "for the services of the Crown" without infringement. Certain exclusive rights of the owner of "copyright material" are qualified by Parliament in order to achieve that purpose. It is the statutory qualification of exclusive rights which gives rise to a statutory quid pro quo, namely a statutory right in the copyright owner (here a surveyor) to seek "terms" upon which the State (excepted from infringement by the legislature) may do any act within the copyright (s 183(5)) and to receive equitable remuneration for any "government copies" (s 183A). With reference to the use by the Spicer Committee of the constitutional expression "just terms", it may be added that CAL conducted its case in this Court on the footing that the statutory scheme afforded "just terms" to copyright owners.

Given that CAL proceeded on the basis that the Crown use of copyright statutory licence scheme was "just terms" under section 51(xxxi), then it is arguable that removing this financial aspect may put such a provision in breach of section 51(xxxi). This may particularly be the case if the government continued to charge for the use of the survey plans. Certainly, as the law currently stands, it is available to the Government to use the fair dealing and other exceptions provided in the 1968 Act (in fact, as noted in the CAL v NSW joint judgment, if these provisions apply, then the statutory licence scheme doesn't - see paragraph [11].) However, would the inclusion of provisions that give the government a free pass to use copyright-protected works created by others, for fulfilment of their statutory obligations and what reasonably flows from those obligations, be valid under section 51(xxxi)?

In conclusion, although I have dedicated a whole chapter in my doctoral thesis to determining the boundaries of the copyright power of the Constitution and the concurrent effect on the Australian public domain, I will admit that future intellectual property cases are less likely to be concerned with section 51(18) and more to do with section 51(31). And, to end on a lighter note, that makes The Castle required viewing for anyone involved in intellectual property!

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, Crown copyright, High Court of Australia, licensing

In the course of the decision, the High Court referred to the position in other jurisdictions with respect to Crown use of copyright works. It cited the UK position under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (UK) and the different types of what it would describe as "free use provisions" under that law. These are exceptions to infringement on the grounds of different types of public administration:

- Section 45 -"Copyright is not infringed by anything done for the purposes of parliamentary or judicial proceedings" and the reporting of such proceedings;

- Section 46 - "Copyright is not infringed by anything done for the purposes of the proceedings of a Royal Commission or statutory inquiry", its reporting and the issue to the public of a report of the Royal Commission or statutory inquiry;

- Section 47 - Where material is open to public inspection due to a statutory requirement or statutory register, copyright is not infringed in a literary work in certain cases and not including the issuing of the work to the public; however pursuant to section 47(2) "copyright is not infringed by the copying or issuing to the public of copies of the material, by or with the authority of the appropriate person, for the purpose of enabling the material to be inspected at a more convenient time or place or otherwise facilitating the exercise of any right for the purpose of which the requirement is imposed" etc.

- Section 48 -The Crown can communicate material to the public in the course of public business, and "copy the work and issue copies of the work to the public without infringing any copyright in the work."

- Section 49 - Material comprised in public records can be copied and supplied to any person without infringing copyright.

- Section 50 - "Where the doing of a particular act is specifically authorised by an Act of Parliament, whenever passed, then, unless the Act provides otherwise, the doing of that act does not infringe copyright."

Even without that distinction, however, another argument rears its head: the constitutionality of introducing such free use provisions. Two sections of the Australian Constitution would arguably be involved: section 51(xviii), which gives the Federal Parliament the power to make laws with respect to "Copyrights, patents of inventions and designs, and trade marks"; and section 51(xxxi), which also provides power to the Federal Parliament to make laws with respect to "The acquisition of property on just terms from any State or person for any purpose in respect of which the Parliament has power to make laws."

I have just realised that this post is getting very long, so it is going to be split into two. Constitutional analysis forthcoming!

Labels: cases, catherine, copyright, Crown copyright, High Court of Australia, licensing

Wednesday, August 06, 2008

Notable quote...

[92] Finally, and importantly, a licence will only be implied when there is a necessity to do so. As stated by McHugh and Gummow JJ in Byrne v Australian Airlines Ltd:Hmmm...I'm sure housemate Catherine will have a few things to say about this one. See Catherine's post about the earlier Full Federal Court decision here."This notion of 'necessity' has been crucial in the modern cases in which the courts have implied for the first time a new term as a matter of law."

[93] Such necessity does not arise in the circumstances that the statutory licence scheme excepts the State from infringement, but does so on condition that terms for use are agreed or determined by the Tribunal (ss 183(1) and (5)). The Tribunal is experienced in determining what is fair as between a copyright owner and a user. It is possible, as ventured in the submissions by CAL, that some uses, such as the making of a "back-up" copy of the survey plans after registration, will not attract any remuneration.

Update: Read analysis from Weatherall here.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

In other copyright news, the Attorney-General's Department has tabled its Review of Sections 47J and 110AA: Copyright Exceptions for Private Copying of Photographs and Films. The Review recommends that no amendments be made to the provisions for the time being, gesturing to the relatively short period of operation of the provisions as one reason for this.

In the UK, 'Mr Modchips' has survived a copyright stoush, with judgement in his favour handed down by the Court of Appeal (Criminal Div). It was found that any alleged copyright infringement would have taken place prior to use of the modchips. It will be interesting to see whether the judgement prompts legislative action, as occured following the decision of the somewhat similar case of Stevens v Sony in the High Court of Australia.

Labels: cases, copyright, infringement, legislation, piracy, review, sophia

Friday, December 07, 2007

"It is not reasonable, or legal, for anybody, fan or otherwise, to take an author's hard work, re-organize their characters and plots, and sell them for their own commercial gain. However much an individual claims to love somebody else's work, it does not become theirs to sell."Rowling previously shared quite a close relationship with the Lexicon and has publicly praised the website. (Read more in this post on Ars Technica).

According to SMH:

"Fair Use Project Executive Director Anthony Falzone said the Lexicon is protected by US rules that have long given people 'the right to create reference guides that discuss literary works, comment on them and make them more accessible.'"

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

It doesn't appear that anything detailed, beyond the report in the Sydney Morning Herald, is up on the Internet about this case yet. More to come as more details emerge.

Labels: cases, catherine, infringement

Wednesday, October 03, 2007

Anyway, the point is, it won't be getting to court because the defendants capitulated. According to Linux Watch, Monsoon Multimedia "admitted today that it had violated the GPLv2 (GNU General Public License version 2), and said it will release its modified BusyBox code in full compliance with the license."

This shows that the system works. The GPL must be clear enough that it is obvious what you can't do. (Okay, there's still some discussion, but on the day to day stuff, everything is going just fine).

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

Monday, June 25, 2007

What's Crown copyright? Crown copyright is essentially government-owned copyright. This means that the government owns the copyright in those particular works, like a company might own copyright, or I own copyright in this blogpost. In addition to general works, governments also own copyright in legislation and case law that is produced by the Parliament or judiciary in that particular jurisdiction. Pursuant to Division 1 Part VII of the Copyright Act, Crown copyright subsists in:

- works "made by, or under the direction or control of the Commonwealth or a State" (section 176)

- works first published in Australia if this first publication is by, or under the direction or control of, the Commonwealth or a State (section 177)

- sound recordings and cinematograph films "made by, or under the direction or control of the Commonwealth or a State" (section 178)

- in addition to these provisions, the Crown owns any copyright materials produced by its employees under the general employment provision contained in the Copyright Act, subsection 35(6).

In 2005, the now-dissolved Copyright Law Review Committee released a report on the Australian Crown copyright provisions and made a number of significant recommendations, including the repeal of sections 176-178 and that copyright in primary legal materials (and a number of other government documents, for example, certain Committee reports) be abolished. The Federal Government is yet to reply to the recommendations made by the Committee.

Is Crown copyright available everywhere? Many countries do not have Crown or government copyright: for example, in the United States, "copyright protection...is not available any work of the United States Government" (17 U.S.C section 105). This means that all government produced works, legislation, case law etc is technically in the public domain (with some scholars arguing that, because of this fact, the 'public domain' takes on an additional significance, because copyright law cannot impede the use and wider reuse of these materials.)

What was CAL v State of New South Wales [2007] FCAFC 80 about? In two words: surveyor plans. Pursuant to a number of NSW statutes, survey plans have to follow certain requirements in order to be registered in NSW. These survey plans are also reproduced for certain purposes by the NSW Government and stored in a database. CAL went to the Copyright Tribunal seeking a determination pursuant to sections 183 and 183A of the Copyright Act as to the amount of royalties that the NSW Government should have to pay to the copyright owners for use of particular plans. However, the State of NSW argued that it was the copyright owner under sections 176 (the plans were made under its direction or control) and 177 (it was the first to publish the plans, therefore, under this section, it owned the copyright). The case was referred to the Federal Court of Australia, where the Full Bench made a determination.

What did the Court find about Crown copyright? The Federal Court found that Crown copyright did not subsist in the survey plans in question under either section 176 and 177. Therefore, the Crown did not own the copyright in these particular plans.

Does that mean the State of NSW lost? The Court found that while Crown copyright did not subsist in the plans, the State was entitled to a licence, beyond what was permitted under section 183 of the Copyright Act, allowing it reproduce and communicate the plan in question to the public. The Court found that the “State is licensed to do everything that, under the statutory and regulatory framework that governs registered plans, the State is obliged or authorised to do with or in relation to registered plans.” (at 158).

What was interesting about the case? To me, the glaring omission was the fact that the court did not discuss the recommendation of the CLRC in its final Crown Copyright report that sections 176 and 177 actually be repealed. There are two issues here. First, it is understandable that the Court may have been reluctant to engage in any discussion of whether the Federal Government should or should not repeal these provisions given that the Government is yet to respond to the review. Second, however, the Court did not even mention the fact that the CLRC had conducted a review into Crown copyright and made a recommendation regarding these provisions. While some may consider that irrelevant to the current point at hand, it seems to me that if you are discussing provisions of the Copyright Act that might not be around in a year, it may be worth mentioning that fact.

Will the decision be appealed? According to this CAL press release, "CAL is considering the decision and will decide on our next move in the next few weeks." Let's all chant softly, "High Court! High Court! High Court!"

How do you know all this?

Copyright Agency Limited v State of New South Wales [2007] FCAFC 80 (5 June 2007)

"Court decides surveyors own copyright in maps and plans", CAL News Release.

Catherine Bond, "Reconciling Crown Copyright and Reuse of Government Information: An Analysis of the CLRC Crown Copyright Review", (2007) 12 Media & Arts Law Review (forthcoming), available on SSRN as part of the UNSW Faculty of Law Research Series here.

Labels: cases, catherine, Crown copyright

Thursday, April 05, 2007

Andres Guadamuz has an excellent analysis of the case over at Technollama, and concludes "I do hope we get a case out of this, as it would be interesting for many different reasons. So, in other words, "fight, fight, fight!"" I have to agree. This type of case, combined with the Viacom v. YouTube case tend to have us intellectual property-types foaming at the mouth, waiting to see what will happen next. Sad, but true.

Hat tip: Technollama and Michael Geist.

Labels: cases, catherine, Creative Commons

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

It's amazing how quickly some things can change and it's definitely a good sign when things do. In his latest, very recent 2007 article, R. Anthony Reese discusses the "new unpublished public domain" and, among other issues, discusses why, for example, some authors or their families might want to keep unpublished material private.

It's amazing how quickly some things can change and it's definitely a good sign when things do. In his latest, very recent 2007 article, R. Anthony Reese discusses the "new unpublished public domain" and, among other issues, discusses why, for example, some authors or their families might want to keep unpublished material private.One of the examples that Reese gives is the estate of James Joyce, who died in 1941. Stephen Joyce, James Joyce's grandson and the controller of his literary estate, is notoriously protective of any unpublished material relating to his grandfather and family and, as this material remains under copyright law, it is easy to control publication of the material. One of the reasons Reese identified for Stephen Joyce being so protective of this material is because of its references to James Joyce's daughter Lucia, who spent some time in a mental asylum.

Between the publication of Reese's article, however, and the last few days, this situation has changed.

Back in 2003, Professor Carol Shloss was working on a biography of Lucia Joyce, titled "Lucia Joyce: Dancer in the Wake", when she was contacted by Stephen Joyce and told she was not permitted to quote from a considerable number of materials still controlled by the Joyce estate. Shloss was forced to make significant alterations to her text and delete many of her opinions conforming to the amount of quotation the Joyce estate considered 'fair use.'

In 2005 Shloss made a private supplemental website containing supporting material which she was forced to remove from the book. The Joyce estate threatened legal action against Shloss if she made the website publicly available. But would the Joyce estate succeed with said legal action?

Enter the Stanford Centre for Internet and Society's "Fair Use Project" ('FUP'). The FUP, which began in 2006, provides legal support on projects designed to "clarify, and extend, the boundaries of 'fair use' in order to enhance creative freedom." In June 2006 FUP filed a lawsuit on behalf of Professor Shloss, in order to establish her right to use "copyrighted materials in connection with her scholarly biography of Lucia Joyce."

Last week, the Joyce estate agreed to enter into a settlement agreement permitting Professor Shloss to publish quotations relating to James and Lucia Joyce electronically, and in a book. This is a particularly significant outcome given the situation identified earlier. In the words of Shloss:

"I fought not just for Lucia and Joyce, whose words had to be taken out of my book, but for the freedom to consider what happened to them and for the freedom of others to respond to my ideas. 'Fair use' exists to foster this liveliness of mind; its measure is in transformation not in a restrictive counting of words. Everyone who worked on this case understood that something far more important than my particular book was at stake in the fight. It was an honor to work with them." (source)

Sources/I Want to Learn More!

Stanford Scholar Wins Right to Publish Joyce Material in Copyright Suit Led by Stanford Law School's Fair Use Project, Digital50.com

An Important Victory For Carol Shloss, Scholarship And Fair Use, Anthony Falzone, CIS

R. Anthony Reese, "Public but Private: Copyright's New Unpublished Public Domain" Texas Law Review, Vol. 85, pp. 585 - 664 (particularly pages 618 - 619), 2007.

Matthew Rimmer, "Bloomsday: Copyright Estates and Cultural Festivals" Script-ed, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 383-428, September 2005

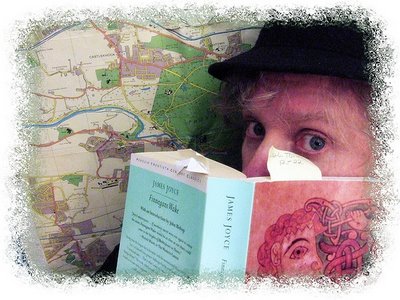

Post written by Catherine Bond and Abi Paramaguru.(Pictured: "365 - Day 32 - Happy Birthday James Joyce!", daryldarko, available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 License)

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

- Analysis by Kim Weatherall here and later here (read about how Australian copyright law is becoming a "strange independent beast")

- Techdirt comments here

- "Copyright Ruling puts Linking on Notice", Sydney Morning Herald, 19/12/06

- "Australian Court Rules against MP3 Link Site", CNet News.com, 18/12/06