Friday, August 31, 2007

More info is available here and here.

Labels: abi, licensing, youtube

Thursday, August 30, 2007

I have to admit that I do tune in occasionally (no pun intended) and yesterday morning, having missed Oz Idol the night before, I checked the "Australian Idol 2007" Wikipedia page to see which singers had gone through. When I checked, only four names should have been listed - two guys, and two girls. However, 5 names were listed under the "Top 12 Finalists" category, even though only 4 names had officially been announced. The fifth name was Ben McKenzie, a 17 year old from the NSW Central Coast. However, later than day, the name had been removed from this page.

Today, however, the name is back - and Ben McKenzie is indeed an Australian Idol 2007 Top 12 finalist (I have checked this against a credible source: the official Australian Idol website). Is this a case of life (or, more specifically, reality TV) imitating Wikipedia? Or is it not only politicians who will stoop to editing Wikipedia pages, but Idol devotees as well?

Wednesday, August 29, 2007

More piracy parody clips from the Revue are available here and here.

Monday, August 27, 2007

Labels: abi, infringement

Friday, August 24, 2007

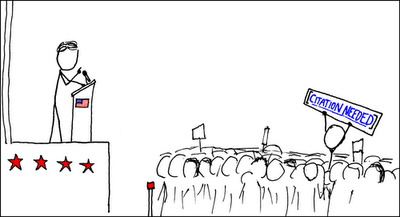

Controversy abounds after newspapers pick up on Wikiscanner and uncover a serious of 'interesting' edits from 'interesting' institutions. The Herald reports that staff from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet have been editing Wikipedia pages, removing material that be damaging to the Government. Opposition leader, Kevin Rudd has criticised Prime Minister John Howard for "engaging public servants to change Wikipedia" rather than personal political staff.

Controversy abounds after newspapers pick up on Wikiscanner and uncover a serious of 'interesting' edits from 'interesting' institutions. The Herald reports that staff from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet have been editing Wikipedia pages, removing material that be damaging to the Government. Opposition leader, Kevin Rudd has criticised Prime Minister John Howard for "engaging public servants to change Wikipedia" rather than personal political staff.Premier of NSW, Morris Iemma is also under fire after it was discovered that someone from within the NSW Premier's Department removed a reference to a controversial outburst made by Iemma in a media conference last year.

WikiScanner, which credits itself for "creating minor public relations disasters, one company at a time" has been utilised to spot some interesting 'salacious edits':

- A Dell employee insisting that visitors 'get an apple'.

- Someone from Pepsi removing the section on 'long term health effects' of Pepsi.

- Exxon underplaying the effects of its oil spill.

Wikiscanner is a searchable database linking anonymous edits on Wikipedia (where IP addresses are displayed in lieu of a username) to organisations with the associated IP address. Issues have been raised with the fact that it can't be evidenced that the IP was used with authorisation.

If you take a look at the Wikipedia entry for Wikiscanner you can see that no one is without safe (BBC reporting on edits, The Times then reporting on edits by BBC staff etc).

Wikiscanner brings an interesting layer of transparency to Wikipedia, and could be useful tool if the results it shows are reliable. Some organisations have already started banning employees from using Wikipedia (this deals with some of the more embarrassing edits). I suspect that others may start using other tools to ensure that edits can not be traced back to them - and continue whitewashing regardless.

Update: 'The best of recent edits' here.

(Pictured: "Wikipedian Protester", Randall Munroe - via his excellent webcomic xkcd, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 license)

Here's the run-down:

- "Softpedia is a library of over 35,000 free and free-to-try software programs for Windows and Unix/Linux,games and drivers. We review and categorize these products in order to allow the visitor/user to find the exact product they and their system needs," from the help page.

- Wikipedia has a page on it, which interestingly says that "it is one of the top 500 websites according to Alexa traffic ranking."

Tuesday, August 21, 2007

The Creative Commons team has just released a very substantial report on the day and its findings, and both the report and further information can be found here.

Labels: catherine, Creative Commons

Monday, August 20, 2007

A 21 year old man from New South Wales has been arrested for recording The Simpsons Movie on his mobile phone and distributing the movie on the internet. The copy of the movie was taken down after around 2 hours however, by that stage, it had been copied many times and further disseminated. It took the police about 72 hours to locate the man and raid his home. The Australian Federation Against Copyright Theft (AFACT) have issued a press release here. Apparently the man is facing up to five years imprisonment. More information is also available in this Sydney Morning Herald article.

A 21 year old man from New South Wales has been arrested for recording The Simpsons Movie on his mobile phone and distributing the movie on the internet. The copy of the movie was taken down after around 2 hours however, by that stage, it had been copied many times and further disseminated. It took the police about 72 hours to locate the man and raid his home. The Australian Federation Against Copyright Theft (AFACT) have issued a press release here. Apparently the man is facing up to five years imprisonment. More information is also available in this Sydney Morning Herald article.I wonder what Comic Book Guy would have to say about all this?

(Pictured: "Congealed Wobbling Blob of Copyright", Abi Paramaguru, Picture is available under either a AEShareNet

Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License.)

Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 License.)Labels: abi, infringement

Labels: catherine, social networking

Thursday, August 16, 2007

At a recent meeting at DEST about the RQF there were some comments made about problems with the creation of the digital repository where all the research material related to submissions made by Universities is to be stored. We were told they were still engaged in discussions and negotiations with publishers over rights.

This got me thinking- Well, rather than engage in discussions with publishers about this arguably non-commercial use of copyright works produced in the Higher ed sector, why not put the energy into drafting a copyright exception? After all, the Act is already full of them in relation to education and simplicity of the Act can hardly be a current goal. I guess there would be issues of retrospectivity for the past RQF period, but not for the future iterations. More law reform might be a more productive use of time and also be in the public interest.

But then I got to thinking- what rights do these publishers supposedly have?

Clearly they have rights to the typesetting of work they publish, but I doubt they are being so specific.

Putting aside completely the question of whether the author or their institutional employer actually own the works in the first place, most authors have book contracts with copyright provisions that are duly signed. But I have written a few book chapters for a number of local and international publishers and never once been asked to assign those rights. In terms of journals, I have only been asked once to sign a copyright agreement, and that one I altered to retain some rights. Most of my colleagues have never signed agreements in relation to the majority of their book chapters and journal articles. Doesn’t case law say that in these circumstances where there is no written agreement the publisher owns no more than a bare licence? If so, why is DEST talking to them about our work and presumably going to pay royalties for the privilege of having access to a copy of them for RQF purposes, taken from the budget that could otherwise go to other more important uses in our underfunded sector?

Labels: guest post

Tuesday, August 14, 2007

I was going to comment on this TechnoLlama post, but then I thought, "why not just blog about it?"

Now, before I go any further, let me reiterate, I am not a lawyer, I have no formal background in law, and the Unlocking IP project is not even particularly about patents.

Get to the point, Ben.

Okay, okay. My point is this, and please correct me if I am wrong (that's why I'm making this a whole post, so you can correct me in the comments): as I understand it, the abstract of a patent does not say what the invention is, but rather it describes the invention. I.e. the abstract is more general that the invention.

For example, say I had a patent for... *looks around for a neat invention within reach*... my discgear. Well the abstract might say something like

A device for storing discs, with a selector mechanism and an opening mechanism such that when the opening mechanism is invoked, the disc selected by the selector mechanism is presented.

But then the actual patent might talk about how:

- the opening mechanism is a latch;

- the discs are held in small grooves that separate them but allow them to be kept compact;

- the lid is spring loaded and damped so that when the latch is released it gently lifts up;

- there is a cool mechanism I don't even understand for having the lid hold on to the selected disc;

- said cool mechanism (the selector mechanism) has another mechanism that allows it to slide only when pressed on and not when just pushed laterally;

- etc.

To go back to the original example, an old vinyl disc jukebox (see the third image on this page) would satisfy the description in my abstract, but not infringe my patent.

In summary, I'm not alarmed by the generality of the abstract in the Facebook case. But if it turns out I'm wrong, and abstract are not more general than the patents they describe, let me just say I will be deeply disturbed.

You have no idea what you're talking about

I thought I made that clear earlier, but yes that's true. Please correct me, or clarify what I've said, by comment (preferred), or e-mail (in case it's the kind of abuse you don't want on the public record).

Friday, August 10, 2007

Andrew Keen has been described by one UK technology journalist as being the possible “Martin Luther” of the Internet counter-reformation. Yet that statement, like the majority of the content in Keen’s recently released book, The Cult of the Amateur, is over-exaggerated. If Keen is to be believed, then the end of culture is nigh and the Internet, Web 2.0, bloggers, noble amateurs, YouTube, Jimmy Wales, MySpace, lonelygirl15, Google, and Wikipedia, are to blame. To Keen, Web 2.0 is a classic example of the “infinite monkey theorem”, where, if you put unlimited monkeys in front of unlimited typewriters, one of the monkeys will eventually produce Hamlet. On the Internet, everyone is a monkey, except, of course, Keen.

Keen ‘confesses’ early on in the book that he pursued the dotcom dream, and that he is “an insider now on the outside who has poured out his cup of Kool-Aid and resigned his membership from the cult” (pp. 11-12). These experiences make him different from the average Internet-user. Over the next 200 pages, Keen provides the reader with colourful, creative, you’ve-probably-heard-them-somewhere-before examples of why Web 2.0 will be the death of creativity and culture. The majority of these examples are, perhaps not surprisingly and disappointingly, United States-focussed. According to Keen, although the Internet has been praised for its democratic underpinnings and the fact that anyone can create their very own Hyde Park soap-box, these features are resulting in the depreciation of the importance and value of ‘experts’ and the impact of traditional media outlets.

I don’t have the time, or the inclination, to tackle everything in The Cult of the Amateur, so I just want to highlight one point. One of the issues that Keen finds most bothersome about Web 2.0 is the fact that individuals are able to remain anonymous, and therefore they will not be held accountable for what they say. Aliases, therefore, are just plain wrong. Keen states that

“Some argue that Web 2.0, and the blogosphere in particular, represents a returnThis is true, but in a number of other cases, individuals have used aliases, or pen names, and no one has thought the less of them for doing so. George Eliot is a classic example; Mary Ann Evans knew that it was unlikely her novels would be taken seriously if publishers or readers knew she was a women, so she chose to publish her novels under an alias instead. Similarly, Emily Bronte, who penned arguably one of the most important novels in English literature, also wrote under the name Ellis Bell. Keen spends the majority of the novel espousing the traditional means of cultural creation but, until very recently, many women were forced to use an alias in order to be considered the equivalent of their male peers in this dominant system. Further, throughout The Cult of the Amateur, Keen repeatedly refers to the dystopian nightmare that exists in the fictional novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, by George Orwell. But Keen fails to point out that Orwell was in fact an alias, a pen name for Eric Arthur Blair.

to the vibrant democratic intellectual culture of the eighteen-century London

coffeehouse. But Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, and James Boswell didn’t hide

behind aliases by debating one another.” (at p. 80)

It is understandable that, on the Internet, an individual may not feel comfortable publicising their name and therefore chooses to use an alias. It is also a shame that individuals use aliases when they are encouraging non-legitimate conduct (for example, defaming another individual). Most importantly, however, let’s remember that aliases are not an Internet-based phenomenon.

There is more that could be said about The Cult of the Amateur: somebody needs to defend Jimmy Wales, and explain why people lie about their age offline too, just like lonelygirl15. However, in conclusion, if you don’t like what Keen is saying about your web, Web 2.0, don’t get mad: get blogging. One day one of us bloggers is bound to stumble into saying something brilliant! Now, where have Pigsy and Sandy gone....?

Labels: book review, catherine

Tuesday, August 07, 2007

Labels: catherine, free software, open source

Monday, August 06, 2007

On the Creative Commons blog, Mike Linksvayer has some interesting comments on a new paper, "Preliminary Thoughts on Copyright Reform" by renowned copyright scholar Pamela Samuelson, and the title for this post comes from Samuelson's paper (at p. 7). As Samuelson rightly notes, copyright law is becoming far too long, confusing, irrelevant and outdated, to the point where "virtually every week a new technology issue emerges, presenting questions that existing copyright rules cannot easily answer" (at p. 1).

Samuelson proposes a model law for a new United States Copyright Act, but also rightly notes that major copyright reform in the United States is highly unlikely to happen any time soon, what with the Iraq war, tax reform, global warming etc being more pressing for the US Congress than copyright issues. This is true, although, for example, extraditing individuals for copyright infringement does have wider ramifications for civil liberties, as readers familiar with the case of Hew Griffiths know.

About a fortnight ago now, the Cyberspace Law and Policy Centre and Linux Australia co-hosted a Law Tech Talk, given by Maureen O'Sullivan. As Abi reported earlier here, Maureen is from the University of Ireland, Galway, and she gave an excellent presentation titled "The Democratic Deficit in Copyright Law: A Legislative Proposal." Maureen's talk centred on the introduction of a Free Software Act (see version 4 of the Act in SCRIPT-ed here) which would operate to protect free software and free/open source software licences.

So it seems that concurrent to the increase in voluntary licensing practices to release copyright content, there is also an growing push towards legislative change as well, either tackling the bulk of copyright law in one go, as Samuelson has suggested, or by an amending act, as O'Sullivan has proposed. Sadly, however, in an Australian context, legislative copyright reform appears to be a long way off. If anything, as shown by the Copyright Amendment Act 2006, our copyright law will only continue to grow in length and bulk, rather than be substantially reformed.

On a final note, we have a tradition here at the House of Commons of publishing the most spot-on comments made about copyright law (remember Senator Andrew Bartlett's "congealed wobbling blob"?) So, finally, here's Samuelson's take: "...the current statutory framework is akin to an obese Frankensteinian monster" (at p. 6).

Not only is that very apt, but it also managed to integrate a reference to a public domain character as well. Nicely done!

Labels: catherine, free software, legislation, open source